Keratoconus/Corneal Ectasia

-

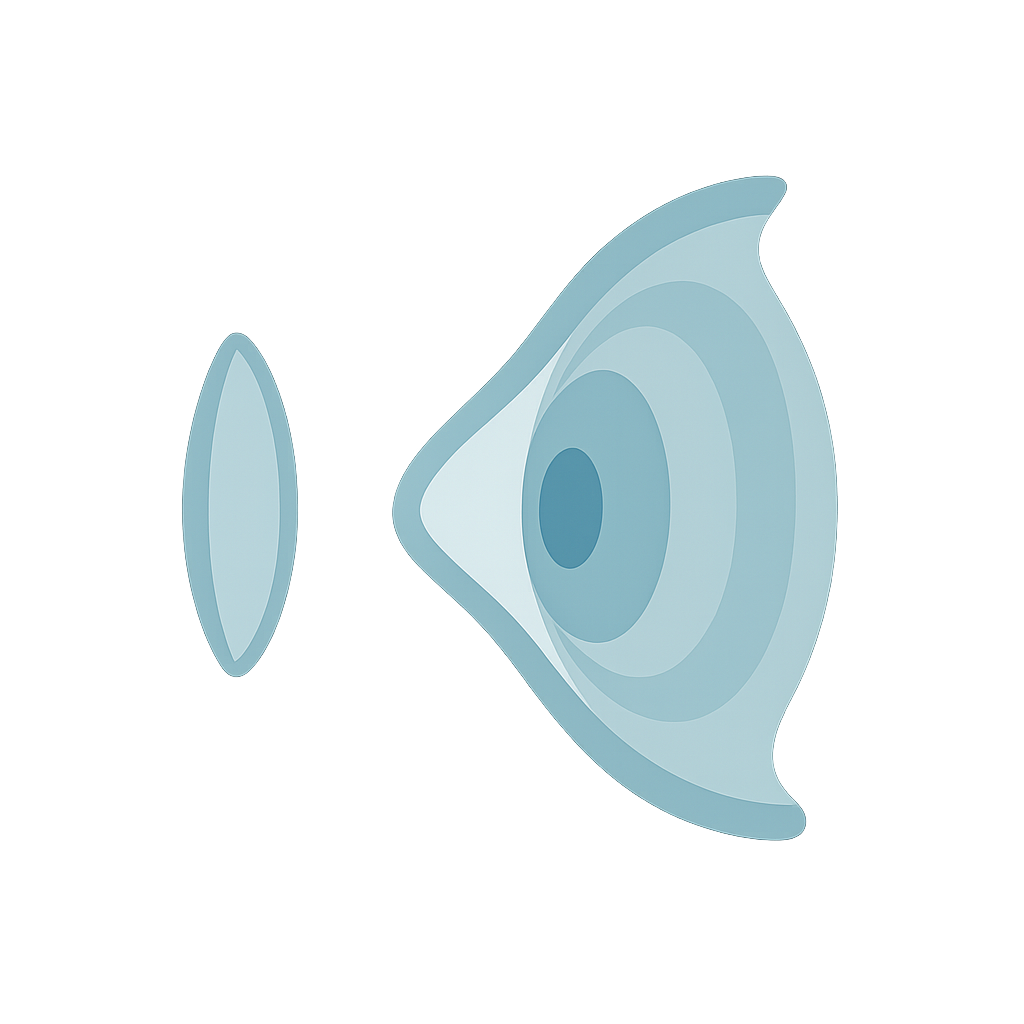

Keratoconus is a progressive eye condition where the normally round cornea (the clear, dome-shaped front window of the eye) becomes thin and begins to bulge into a cone-like shape. This irregular shape prevents light from focusing properly on the retina, leading to distorted and blurred vision.

Keratoconus usually begins in the teenage years or early adulthood, although it can appear earlier or later. The condition often progresses for 10–20 years before stabilising (CLEK Study Group, 2001). It affects both eyes in the majority of patients, though one eye is often more advanced than the other.

Who is at Risk?

Keratoconus can affect anyone, but research shows it is more common in:

People with a family history of keratoconus (Wang et al., 2010)

Individuals with allergic eye disease such as hay fever, eczema, or asthma (McMonnies, 2009).

Patients with certain genetic conditions such as Down syndrome or connective tissue disorders.

Environmental Triggers

Several external factors are known to influence the onset or progression of keratoconus:

Eye rubbing: One of the strongest modifiable risk factors. Vigorous or frequent eye rubbing is associated with worsening corneal thinning and steepening (McMonnies, 2016).

Atopy and allergy: Chronic itching and inflammation increase the likelihood of rubbing, which accelerates damage (Spoerl et al., 2007).

Ultraviolet (UV) exposure and oxidative stress: Suggested to contribute to structural weakening of the cornea (Karamichos et al., 2014).

Other Forms of Corneal Ectasia

While keratoconus is the most common form, there are other ectatic corneal disorders that share similar features:

Pellucid Marginal Degeneration (PMD): Thinning occurs in a narrow band near the bottom of the cornea, leading to a different distortion pattern compared to keratoconus (Srivannaboon et al., 1998).

Post-surgical ectasia: After corneal refractive surgery such as LASIK, the cornea can sometimes weaken and bulge, producing a keratoconus-like condition (Seiler et al., 1998).

-

Managing keratoconus is about more than correcting vision — it’s about identifying the factors that drive progression and applying the right treatment at the right stage. At WA Eyecare, we follow a structured approach that combines careful monitoring, early intervention, and long-term rehabilitation.

1. Identifying Underlying Triggers

The first step is recognising and addressing risk factors that may be making keratoconus worse. The most important of these is eye rubbing, which is strongly linked to faster disease progression. Eye rubbing is often a response to allergic eye conditions such as hay fever or eczema. By controlling allergy and inflammation, and by coaching patients to avoid rubbing, we can reduce one of the biggest risks for corneal damage.

2. Referral for Corneal Cross-Linking

For younger patients, or anyone showing signs of progressive keratoconus, we work closely with ophthalmologists to consider corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL). This procedure uses ultraviolet light and vitamin B2 (riboflavin) to strengthen the cornea, slowing or halting further thinning (Wollensak et al., 2003). CXL does not cure keratoconus, but it is the most effective method available to preserve vision and prevent worsening.

3. Monitoring With Advanced Imaging

Accurate monitoring is essential, since keratoconus can progress unpredictably. We use tools such as corneal topography (mapping the shape of the cornea) and pachymetry (measuring corneal thickness) to establish a baseline. Regular follow-ups then allow us to detect even subtle changes over time, so we can act quickly if the condition worsens.

4. Vision Correction and Rehabilitation

Even with stabilisation, many patients require specialised vision correction:

Glasses may be suitable in the very early stages.

Specialty contact lenses (rigid gas permeable, scleral, or hybrid designs) are often the mainstay of vision rehabilitation, providing clear, comfortable vision by masking corneal irregularities.

Surgical options such as intracorneal ring segments or corneal transplantation are reserved for advanced cases where lenses or glasses are no longer sufficient.

-

Once keratoconus has been diagnosed, the next step is to focus on restoring clear, functional vision. Treatment is tailored to the severity of the condition, the shape of the cornea, and the patient’s lifestyle needs. At WA Eyecare, we combine advanced technology with years of specialty lens fitting experience to provide a full spectrum of options.

1. Corneal Cross-Linking (CXL)While not a vision correction treatment by itself, corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL) is often the first step in managing keratoconus if progression is detected. CXL helps to strengthen the corneal tissue and stop further deterioration.

Cost in WA: In the private system, CXL typically costs around $2,500–$3,000 per eye depending on the provider.

Public hospital access: In certain cases, CXL may be available through the public system (e.g. at Perth’s major teaching hospitals), but waiting times and eligibility criteria apply.

We guide our patients on referral pathways and help determine whether public or private access is more appropriate.

2. Rigid Gas Permeable (RGP) Lenses – Corneal Lenses

For many patients, the most effective way to regain good vision is through RGP contact lenses, which sit directly on the cornea and mask irregularities by creating a smooth optical surface.

Topography-guided design: We use corneal topography software to design lenses that match the unique shape of your cornea. When the cornea is not too distorted, this method often results in an excellent fit within just a few visits.

Clear and sharp vision: RGP lenses can provide clarity that glasses cannot, as they neutralise the distorted corneal shape.

3. Trial Fitting When Topography is Limited

In some cases, keratoconus makes the cornea too irregular for reliable computer-guided design. In these situations, we use a hands-on trial fitting process:

Special trial lenses are placed on the eye.

A coloured dye called fluorescein is instilled. Under a blue light, this highlights how tears flow under the lens.

Based on the dye pattern, we adjust the curve and shape of the lens bit by bit until the best fit and vision are achieved.

This method is more time-intensive but remains highly effective for advanced cases.

4. Larger Diameter Lenses – Scleral Lenses

If corneal RGP lenses do not provide stable vision or comfort, scleral lenses may be recommended.

These are larger rigid lenses that vault over the cornea entirely and rest on the white part of the eye (the sclera).

Because they create a tear-filled reservoir between the lens and the cornea, scleral lenses can mask severe irregularities and provide exceptional comfort and vision.

Sclerals are often the best option for advanced keratoconus, severe distortion, or patients who have failed with other lens types.

5. Comfort and Work Environment

While RGP and scleral lenses deliver excellent vision, they can sometimes feel less comfortable than soft lenses — particularly for patients working in dry or dusty environments.

Piggyback lenses: In some cases, we place a thin soft lens underneath an RGP lens, creating a cushioning effect for improved comfort.

Scleral lenses: These avoid direct contact with the cornea altogether, making them more comfortable in challenging environments.

Of course, each method has its own challenges (e.g., longer handling routines, increased lens care), but for most patients, the improvement in vision makes it worthwhile.

6. Cost and Timeframe

Specialty contact lens fitting is more involved than standard lenses and requires multiple visits for assessment and adjustments.

At WA Eyecare, we usually estimate a 2–3 month period from the first fitting to achieving a stable, comfortable result.

The cost is generally $1,500–$2,000 for a pair of lenses (right and left eye), and around half that if only one eye requires fitting.

Fees cover not just the lenses, but also the professional time, trial fittings, and aftercare needed to achieve the best outcome.

We are transparent about costs and discuss them fully before you commit to treatment. While these lenses represent an investment, they provide a life-changing improvement in vision and quality of life for patients with keratoconus.

-

Keratoconus is not always an isolated condition. In many patients, it is linked with other eye or health issues that can contribute to its development or progression. The most common association is with allergic eye disease - people who suffer from hay fever, eczema, or asthma are more likely to have itchy eyes and to rub them. Repeated eye rubbing has been strongly linked to the progression of keratoconus.

Certain genetic and connective tissue disorders also increase the risk. These include Down syndrome, Marfan syndrome, and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, where the body’s collagen structure is weaker. Because the cornea is largely made of collagen, these conditions can make it more vulnerable to thinning and distortion.

Sleep apnea and floppy eyelid syndrome have also been associated with keratoconus. These conditions can cause mechanical stress on the eyes during sleep and are more common in patients with keratoconus.

In addition, keratoconus sometimes appears alongside systemic inflammatory conditions. Chronic inflammation may weaken the cornea’s structure and accelerate changes over time.

Recognising these associations is important, because managing underlying conditions — such as treating allergies to reduce rubbing, or screening for systemic issues — can play a key role in stabilising keratoconus and protecting vision.

-

At WA Eyecare, we welcome referrals for keratoconus and other ectatic corneal conditions. Our philosophy is to provide evidence-based, realistic, and patient-centred care, while supporting referrers in the long-term management of these complex cases.

Contact Lens Options: Nuances and Limitations

While scleral lenses have become an increasingly popular option for advanced keratoconus, they are not a “one size fits all” solution. Although comfortable and capable of masking severe irregularities, scleral lenses can be associated with reduced oxygen transmission, risking corneal neovascularisation, and may present challenges such as midday fogging or handling difficulties for some patients. Careful case selection and follow-up remain critical.

Rigid gas permeable (RGP) lenses should not be dismissed as universally uncomfortable. Modern high-Dk daily disposable lenses can be used in a piggyback system to cushion the cornea and reduce awareness, particularly for patients in dry or dusty environments. This approach allows us to maintain optical quality without compromising patient tolerance.

Holistic Care Considerations

Keratoconus patients, like all patients, will often experience dry eye symptoms over time. In those wearing RGP lenses — especially when combined with allergic eye disease — ocular surface monitoring is essential. Addressing dry eye and allergy management early can improve lens tolerance and long-term outcomes.

Even with contact lenses, patients benefit from having an up-to-date spectacle prescription. Glasses may not provide functional vision in all cases, but they can support patients when lenses cannot be worn, such as during illness, allergy flare-ups, or simply to meet driving requirements.

Setting Realistic Expectations

RGP lenses do not always restore patients to 6/6 vision. Often, the goal is to take patients from non-functional vision to a level where they can work, study, or drive safely. Setting realistic expectations is key to patient satisfaction.

Recent advances in scleral lens technology are helping bridge this gap. Features such as micro-vaults allow lenses to vault over localised irregularities (e.g., pterygia), while wavefront-guided designs can incorporate aberration control to improve contrast sensitivity. In some cases, multifocal segments can be built into scleral designs, enhancing reading vision without sacrificing stability.